Backstage at the Conan O’Brien show, journalist Drew Tewksbury met up with band Young the Giant in the moments before they go onstage before a television audience. The article was featured in the Spring issue of Nylon Magazine in 2014.

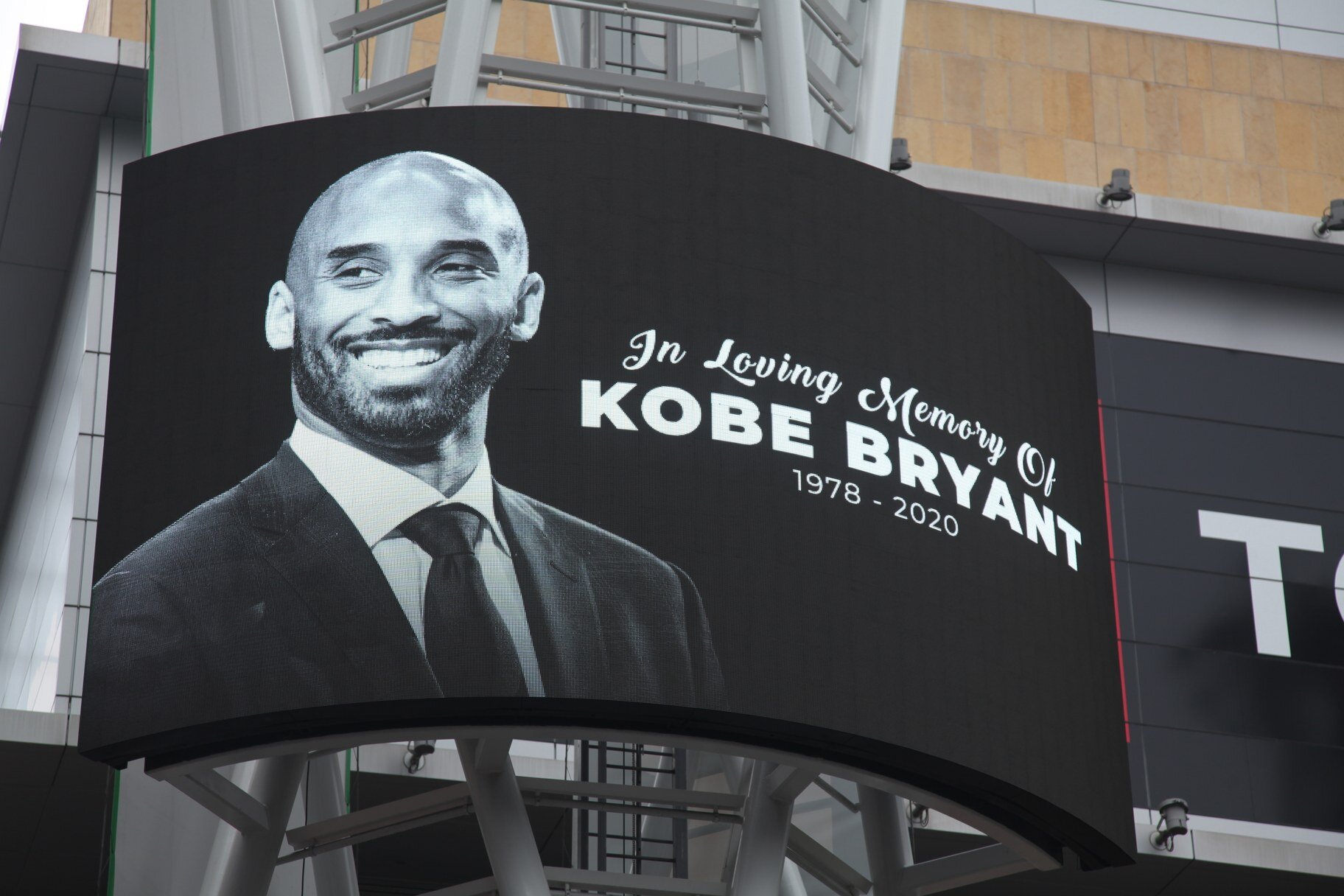

Kobe Bryant memorial at LA Live draws hundreds of mourners

Sergio Carrillo holds a Kobe Bryant street sign. Photo by Drew Tewksbury for KCRW.

Published on KCRW Jan. 26, 2020.

The streets of downtown Los Angeles were awash with color on Sunday. As the Grammy Awards drew famous musicians clad in tuxes and sequins to the Staples Center, hundreds of people wearing purple and yellow jerseys descended on the plaza at the adjacent LA Live, where an impromptu memorial for legendary Laker Kobe Bryant had coalesced.

Bryant died early Sunday morning in a helicopter crash in Calabasas, Calif., alongside his 13-year-old daughter Gianna Maria Onore Bryant, and seven others.

Attendee Alex Prado told KCRW's Angel Carreras that he was shocked when he heard the news about Bryant. "The world just stopped for that second that I heard, you know, [I] got real sad. I grew up as a Kobe fan. Just hearing somebody so iconic [is] gone: It just really stops time."

Under digital billboards lit up with Bryant's face, the solemn crowd was nearly silent; some held basketballs, while others carried yellow flowers, which were placed on a makeshift altar. The quiet was occasionally broken with chats of "Kobe" and "GiGi," the nickname of Bryant's daughter. Others held homemade signs paying homage to Bryant, like Sergio Carrillo, 25, who held a street sign emblazoned with the late Laker's name.

"[Kobe's] someone I looked up to," said vigil attendee Jesse Ramirez. "He's like a god in Los Angeles. [We] lost Nipsey [Hussle]. Now they lost Kobe. It's really, really devastating."

Nearby, Grammy attendees — who were walking from the neighboring Marriott hotel lobby to the Staples Center — permeated crowd of mourners, offering a moment of stark contrasts: a collective moment of tragedy interwoven with a celebration of creativity.

Floating Through The Air With Liam Hemsworth

The Perfect Time to Rediscover Robert Mapplethorpe

Performance Artist Rafa Esparza Is Fighting Invisibility, One Brick at a Time

Riding Along With Talulah Riley

‘Game of Thrones’ Star Alfie Allen Understands Anguish

Anoushka Shankar links songs of India and Spanish flamenco

Workaholics Star Blake Anderson's T-Shirt Line Makes You Go "WHAAAAT?"

Getting Big With Eric "McSteamy" Dane

Behold the Idyll-beast, the Bigfoot of Idyllwild

Idyll-Beast, the Bigfoot of Idyllwild, has been photographed in the wild, skulking between the pines, like Chewbacca with a hangover.

This Seaside Baja Town is Wilder than Star Wars' Cantina

Whole fish cooked Zarandeado-style; Credit: Courtesy Club Tengo Hambre

Published as part of LA Weekly’s Travel Issue 2016, which I edited.

At the height of Mexico’s cartel violence in the mid-2000s, Baja became a no-go zone to American tourists, who refused to cross the California border. In recent years, however, the region has settled down and undergone a transformation with the opening of craft breweries, trendy restaurants and galleries in Tijuana. Just an hour and a half south, Baja’s beautiful Valle de Guadalupe wine country has become a hotbed of culinary and oenological bounties. The Valle’s Ruta del Vino showcases Mexican modernist architectural marvels and boutique hotels tucked among vineyards frequented by telenovela starlets and San Diego pensioners.

But with its newfound popularity, Baja also has lost many of its traditional haunts, which have been replaced by gastronomically adventurous experiments. If you’re searching for the real gem of classic Baja, though, look no further than Popotla, a rough-and-tumble fishing village just a 20-minute drive south of spring-breaker hot spot Rosarito.

The small but bustling town is perched like a barnacle alongside Baja Studios, a 51-acre oceanside movie lot where the mega-blockbuster Titanic was shot in 1996. While the studio is well past its heyday, Popotla rages on — literally in its shadow. Avoid the town’s shoddy, thatched-roof restaurants and head down to the surf, where the real anarchic action is. Food here is best served under an open sky — and straight from the sea.

Although the area is Anthony Bourdain–approved, there’s no buttoned-up elegance here. If fanciness is what you seek — if you’re a little fresa, as it’s said in Mexico — then stay in Alta California. Here in Popotla, it’s all about rustic flavors and a rugged feel.

Use a smooth river rock to crack open crab legs; Credit: Courtesy Club Tengo Hambre

Try any one of dozens of stalls, each serving up its own spin on al fresco feasts. Shirtless cooks lord over oil-drum grills that cast a smoky veil as fresh lobster, shrimp or octopus roasts upon the flames. Order from a laminated menu, and a woman will come by with a whole snapper or rockfish for inspection. Give a thumbs-up and out comes the machete to fillet it. Onto the mesquite fire it goes. The fresh dish is prepared Zarandeado-style, slathered with garlic and ancho chile powder, rendering it as red as the tomatoes that garnish it. At foldout tables draped with torn awnings, sit elbow to elbow with wizened abuelas and their grandkids, or alongside surfer bros with sunglass tans as they sip Modelos and scarf fish bits with their bare hands.

Pay no attention to the cars parked on the beach, the tide rushing under their tires. Never mind the funky bathroom sitch. And ignore the lack of luxe comforts; they have no place here on the edge of the world. Instead, enjoy the procession of spectacles that surrounds you. Listen to the sounds of kids laughing at a clown who has wandered up, conjuring roses from squeaking balloons. Witness a pair of seals flopping onshore, begging for a spare mackerel, and a little attention, from strolling diners walking off a ceviche-and-frijoles lunch.

If you’re lucky, a baby hippo–sized pig may make a cameo, politely squeezing between the red plastic chairs as her pink fuzzy skin brushes against your leg, then snuffing her snout in the warm sand, searching for scraps. The friendly creature is anything but tomorrow’s carnitas; she’s Filomena, the swine queen of Popotla, whose free-roaming antics are welcomed by all with an almost royal reverence.

Amid the clamor of honking car horns, cracking beer cans and youngsters playing in puddles, there is something peaceful about it all, something almost ancient, that triumvirate of experiences uniting sun-drenched beaches around the world: fish, fire and friends. What more do you need?

POPOTLA, MEXICO

Getting there: Cross the border and drive toward Playas de Tijuana, where you can perhaps grab a seaside michelada, then follow the coastline 1D federal highway for about 40 minutes. You’ll pay a few tolls along the way, but the view of the Pacific is unbeatable. Before you go, remember to pack your passport and pick up Mexican car insurance on the American side, before crossing. Expect a long line on the border on the way back. But the memory of ceviche on the beach is well worth the wait.

What to do: Spend the afternoon sampling traditionally prepared seafood, watching dolphins jump from the water and taking in other aquatic scenes you’ve seen only in tramp stamps and Lisa Frank trapper-keepers. When you’ve had your fill of beer and sunshine, visit the row of furniture shops, featuring insanely inexpensive, handmade works by local artisans.

Where to eat: The offerings are nearly endless. Focus on certain dishes and experiences that are indigenous to the area, such as using a smooth river rock to crack open crab legs (those primordial foodies of the caveman era were onto something).

Where to stay: Skip the nearby resorts and Airbnb a Rosarito beach house. There’s also the funky surf hotel La Fonda, which is an unpredictable but often fun option, with a gargantuan buffet that would make even aspiring gluttons blush. If you want a que romantico weekend, stay at Cuatrocuatros near Ensenada, at the entrance to Baja wine country. Here, visitors sleep in sleek tent cabins positioned among the vines and can ride mountain bikes between the hulking hulls of landlocked fishing boats positioned throughout the expansive campus.

Wild card: Visit the nearby Baja Studios to pay homage to Leo and Kate at the compound’s Titanic museum. Re-enact key scenes and, if the spirit compels you, perform an impromptu Celine Dion song or two.

Pierre Huyghe's Unpredictable Ecosystems at LACMA

The Strange But True Story of How the Hip-Hop Collective Odd Future Hit the Big Time

WRITING THE TRAINS: GRAFFITI ON FREIGHT CARS

Inside the Museum of Jurassic Technology

The Museum of Jurassic Technology of Los Angeles challenges the traditional museum. Instead of acting as a source of knowledge, the museum raises more questions than answers: Is it a repository for the obscure, the ephemeral and the unfathomable, encapsulated in a post-modern Victorian salon of the 21st century?

Worndown + Threadbare: The (not so) Secret Lives of Los Angeles Garment Workers

Detail from the two-page spread in Flaunt Magazine

Published Flaunt Magazine 2008.

For Lupe Hernandez, it all started with a plane ticket. As the youngest child living with six brothers, she found herself a servant in her own household in Mexico City, having taken the place of her mother, who died when Hernandez was only 13. Her father, a street sweeper and an alcoholic, offered her little support, so when Hernandez’s sister in the States offered her a ticket to Tijuana, and a chance to join her in Los Angeles, Hernandez jumped at the opportunity. After landing in Tijuana—essentially a wide-open Ellis Island for undocumented immigrants—and almost a thousand miles from her home, she searched the streets for a coyote, or smuggler, which did not take long. Hernandez and a small group were led to the border, where they crossed into San Diego, on foot, only to be arrested by police on the other side.

She was jailed for a day, but would not be deterred. “I didn’t care how many times they would catch me,” she says. “I wouldn’t ever go back to my house.”

Hernandez left Mexico City on a Wednesday. Five days later, she had crossed the border into the United States and found employment at the garment factory where her sister worked. Hernandez was 17 years old then, and for the last fifteen years, has labored in garment factories and sweatshops in Los Angeles. She says that some employers treated her well, while others forced her to work in unsanitary conditions, locked her in, denied her water, and refused her access to the bathroom. Once again, enough became enough.

This is not a story with a happy ending; one that wraps up neatly with the bad guys being punished and the underdogs prevailing. We are catching up with this story, in media res, as the 21st century dawns and the gears of globalization restructure how we manufacture and distribute goods. But at the human level of this transition is Lupe Hernandez and millions of women like her.

As Hernandez says, her story is “muy, muy típico.” According to a recent study by the Pew Hispanic Center, there are an estimated 12 million undocumented male and female workers in America, today. “Immigrants come to this country and we think that there are a lot of jobs,” Hernandez says. “Well, there are many jobs, but they’re jobs of exploitation.”

For many undocumented people in Los Angeles, garment work provides entry into this underground economy, offering those who don’t speak English, or with little work experience, a quick way to make some money. But for those who work in the sweatshops, their efforts are anything but lucrative. Around 67 percent of Los Angeles factories that produce clothing pay their employees less than minimum wage, according to a study, in 2000, by the U.S. Department of Labor. But this is no secret. It is tacitly understood that the people who make the products that Americans consume, including, and especially, the clothes we wear, are probably exploited and underpaid, but we look the other way. After all, the backbone of the American economy was forged by slavery and a model of capitalism that bases its structure on the fact that somewhere in the line of production, someone is not being paid, or is being paid very little.

It’s what U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, in 1933, called “the race to the bottom,” a global economy, where employers in an unregulated market continually lower their employees’ wages in order to stay competitive, which would cause their competitors to lower their workers’ wages in response, and so on. This plummeting of wages could then reach a theoretical zero point, where employees’ pay would potentially fall to zero.

Stories about sweatshops don’t often appear in the mainstream media. Why cover sweatshops as “news,” when they’re the norm? During the era of Progressivism, Jacob Riis’s photographic reportage of the tenements on New York’s Lower East Side, at the turn of the century, and Upton Sinclair’s novel, The Jungle, opened our eyes to the plight of the lower class. In 1995, sweatshops re-entered the media’s viewfinder when authorities discovered an apartment complex of nearly seventy Thai garment workers, some who had been enslaved for up to 17 years, in the sleepy L.A. suburb of El Monte. The workers were housed in an apartment complex, with ten people packed into a room built for two. They worked eighteen-hour days, surrounded by barbed-wire fences and armed guards, as they sewed clothes for some of the biggest retail chains in the country. The media coverage of this human-rights violation reinvigorated the anti-sweatshop movement in Los Angeles and brought awareness to the embarrassing revelation that some retailers were manufacturing clothes without concern for the people who did the backbreaking work. And for those at the top of the retail chain, it seemed that blissful ignorance and denial was de rigueur.

When Spanish filmmaker Almudena Carracedo first came to the U.S., she couldn’t understand how one of the richest countries in the world could still use sweatshop labor in the 21st century. She set out to make change by documenting the lives of three garment workers in Los Angeles. What was supposed to be a short project turned into last year’s PBS feature, Made in L.A., which focuses on workers in Los Angeles’ garment district, who are organizing against one of the biggest perpetrators of workers’ rights violations in the city: Forever 21, a retail chain popular among teens for its inexpensive, disposable fashions. “The goal of the film was to show what it was like for people at the bottom,” Carracedo says. “It provides a window into the lives of those who make our clothes, and to humanize their story—to make them not seem like just a number.” While shooting footage of a garment workers’ protest, Carracedo approached a woman in the crowd for a quick on camera interview: Lupe Hernandez.

“My mother was paid around a dollar for every dress she worked on,” says Lee, “which would retail for about $99, so she made about one percent of the garment’s end cost. Keep in mind, this was the seventies, and that’s about the same that workers make today.”

In her documentary, Carracedo traces the evolution of garment workers Maria Pineda, a struggling mother; Maura Colorado, an El Salvadoran who, in eighteen years, hasn’t seen the sons she left behind; and the charismatic Hernandez, as they attend classes at the Garment Worker Center, at the edge of the Fashion District.

The Center is embedded in a small building near Santee Alley—a bustling street where vendors hawk Prada-like bags, Gucci-esque sunglasses, and other faux fashion—and acts as both a respite from the harsh conditions of the factories and a place to organize for workers’ rights. The director of the Center, Kimi Lee, whose mother is a Burmese ex-garment worker, understands the hardships and the stress that sweatshops foster.

“My mother was paid around a dollar for every dress she worked on,” says Lee, “which would retail for about $99, so she made about one percent of the garment’s end cost. Keep in mind, this was the seventies, and that’s about the same that workers make today.”

After three years of organizing boycotts and protests against Forever 21—spreading the word on street corners and filing lawsuits for back wages—the clothing corporation settled the case organized by the Garment Worker Center. Victory, at last. But this isn’t the end of the story; it’s the beginning of a larger battle for the rights and dignity of all workers. Lupe Hernandez is now on the front lines of this fight, working as an organizer for Sweatshop Watch, and helping to educate workers on ways to break the paradigm of exploitative labor.

“The more that I learn, the lonelier I feel,” says Hernandez, in the film. “Ignorance protects you, but I realize I’ve come this far and no one can take that away from me.”

Abusing The Threshold: Turning the Screws of Los Angeles’ Experimental Noise Scene

Since 1998, The Smell has hidden itself in the shadows of downtown L.A.’s skyscrapers, as the big-budget venues of Hollywood nightlife provide a distraction for tourists and taste-making poseurs, allowing it to remain an accessible, all-ages venue dedicated to free-form experimentation and the DIY ethic.